HYDERABAD, Pakistan: On her 99th birthday in May 2017, Dharam Mukhi sat thousands of miles away in the United States when her family unveiled an extraordinary gift: a video chronicling three centuries of the Mukhi family’s legacy and the painstaking restoration of her childhood home in Sindh, Pakistan.

The video brought back the carved wooden galleries, the Italian cupola and the marble staircase of the mansion she had left behind when her family left Hyderabad during the Partition of the Indian Subcontinent in 1947 and the violence and upheaval that followed.Â

“I feel like I am back home,” she told her son, Dr. Suresh Bhavnani. Twenty days later, she passed away.

Dr. Suresh Bhavnani, along with other members of the Mukhi family, visits Mukhi House in Hyderabad, Pakistan, on January 29, 2013. (AN photo/Suresh K. Bhavnani)

The picture taken on August 20, 2025, shows Mukhi House in Hyderabad, Pakistan. (AN photo)

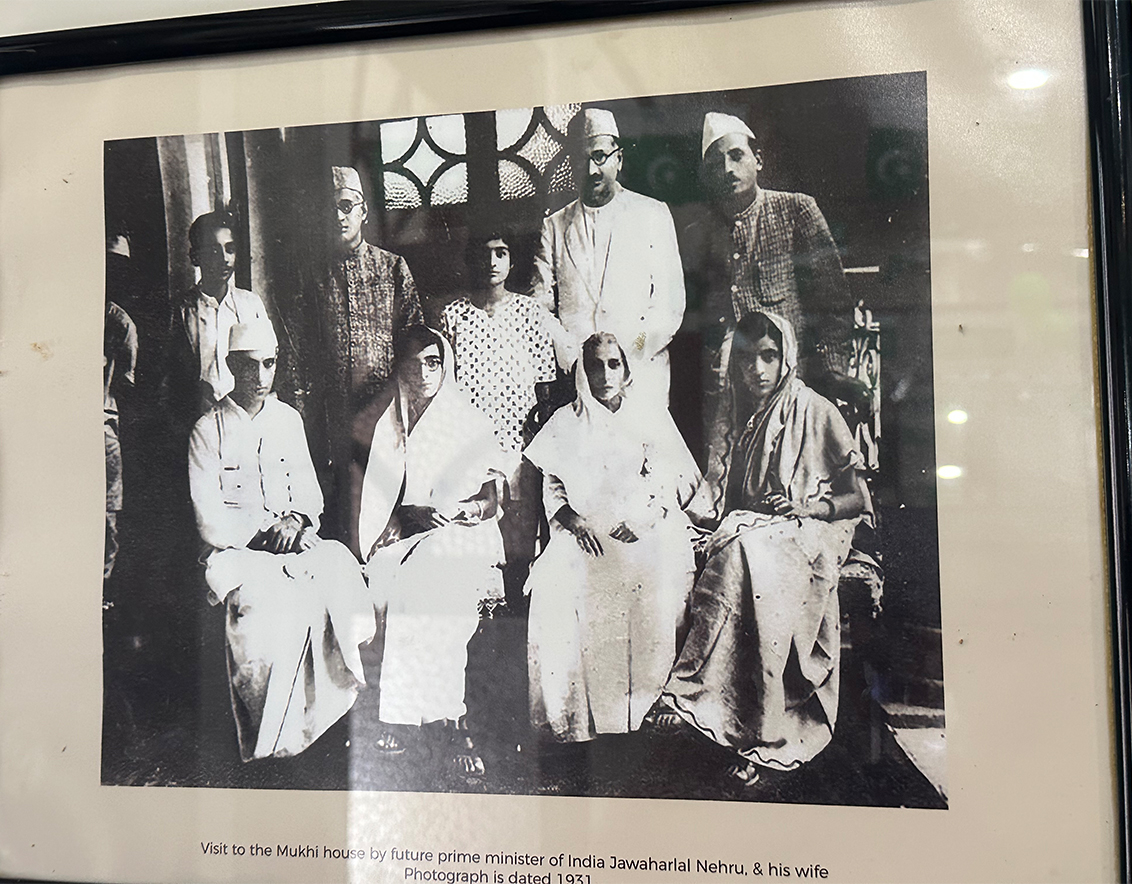

Built in 1921 by her uncle Jethanand Mukhi, a Hindu politician and philanthropist, the three-story Mukhi House was more than a residence. With its Corinthian columns, mosaic floors, stained glass, and frescoed walls, it stood as a palace at the heart of Hyderabad. Its halls hosted luminaries of the era — Indian National Congress leader Jawaharlal Nehru and Sindh’s pre-Partition chief minister, Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah, among others.

“They considered it a palace, not just a house,” said historian and archaeologist Dr. Kaleemullah Lashari, who later led its restoration. “They built it with that vision and lived in it to the fullest.”

The photo, taken on August 20, 2025, shows a picture of Hyderabad city in 1900, located at the Mukhi House in Hyderabad, Pakistan. (AN photo)

After Jethanand’s death, his brother Gobindram Mukhi, Dharam’s father, carried forward the family’s civic leadership. He was elected to the Sindh government as a voice for the Hindu community, despite threats and assassination attempts.Â

But Partition forced the Mukhis to move their children to Bombay while Gobindram and his wife returned frequently to manage affairs, clinging to the hope of resettling in Hyderabad.

That hope ended abruptly in 1957 when Gobindram died in a road accident near Thatta. The family never returned. The mansion, once the jewel of Hyderabad, was reduced to decades of disrepair. It became a government office, then a girls’ school, then a paramilitary checkpoint.Â

Fires, neglect and scavengers stripped it of its grandeur.Â

“Its vital structural elements had grown weak,” Lashari recalled of his first visit to the decaying building.”

The photo taken on August 20, 2025, shows a picture of former Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and his wife visiting Mukhi house in 1931 in Hyderabad. (AN photo)

The Mukhi family, still in possession of the property papers, offered the house to the people of Sindh on one condition: that it be conserved and turned into a museum.Â

Declared a heritage site by the Sindh government, restoration began in 2009. The work was arduous, from sourcing tiles to match originals to recreating stained glass, and training artisans to revive lost techniques.

By 2013, the house had been restored to its former glory, though bureaucratic inertia kept it closed to the public for years. From the US, Dr. Bhavnani campaigned to keep the project alive, circulating videos such as Legends of the Mukhi House and urging Sindhi youth to reclaim the site as part of their cultural inheritance.

“When the place was finally turned into a museum and inaugurated, I credited my late grandfather with inspiring my persistence,” Dr. Bhavnani said. “He was living the role of a Mukhi who had promised to serve the community that had elected him, and who were now vulnerable as they had chosen to stay back in Sindh.”

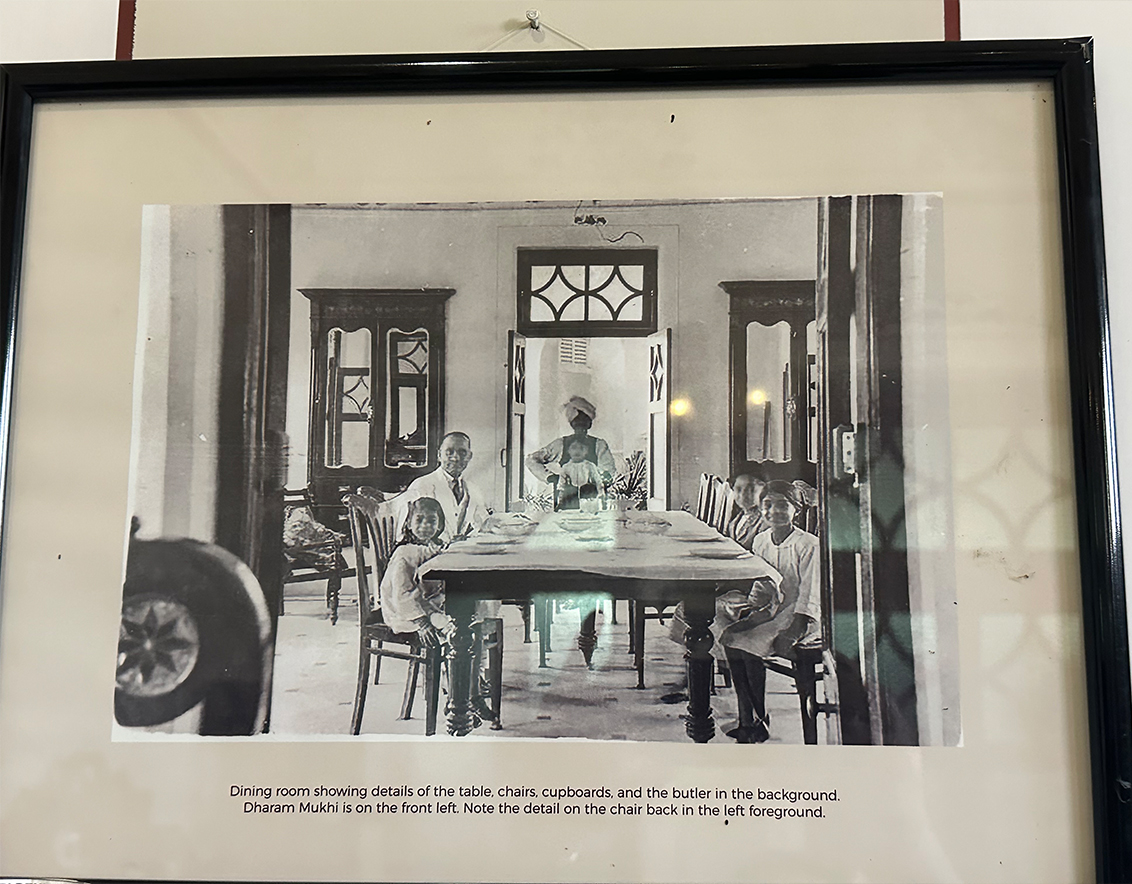

The photo taken on August 20, 2025, shows Dharam Mukhi sitting at a dining table at the Mukhi house in Hyderabad. (AN photo)

The photo taken on August 20, 2025, shows a dining table at the Mukhi house in Hyderabad. (AN photo)

Today, the museum preserves not just architecture but memory. Dharam’s photographs line the first floor: her beside the family’s first car, near Hyderabad’s first telephone, at garden parties with colonial administrators.Â

“We have displayed her photographs in the museum as part of the exhibition,” said Naeem Ahmed Khan, a museum official.

Schoolchildren now walk through its sunlit galleries where once statesmen and reformers debated Sindh’s future.Â

For Lashari, the building is a symbol of generosity across borders and generations:Â

“Just think about how noble the purpose is. A family, which no longer resides here, agreed … to allow their property to be turned into a museum for the benefit of the general public.”